If you’re worried about a short luteal phase and its impact on your fertility, you’re not alone. The luteal phase, the time between ovulation and your next period, plays a crucial role in supporting early pregnancy. A short luteal phase, typically less than 10 days, can make it harder for an embryo to implant and thrive, raising concerns about conception and early pregnancy loss. Research shows that this issue is common among people experiencing infertility or irregular cycles, and it can be linked to hormonal imbalances, stress, intense exercise, or underlying health conditions.

Understanding the causes of a short luteal phase is the first step toward finding solutions. Hormonal shifts, such as low progesterone or altered levels of FSH and LH, can disrupt the development of the uterine lining needed for implantation. Other factors, like high prolactin levels or sudden changes in exercise routines, may also play a role. While treatments like progesterone supplementation are often discussed, evidence for their effectiveness is mixed, and a thorough evaluation is essential to identify and address any underlying issues. You deserve clear answers and compassionate support as you navigate your fertility journey.

- What is considered a short luteal phase, and how can you tell if yours is too short?

- How long is “normal”?

- Why does the corpus luteum set the clock?

- How can you measure your own luteal phase?

- Why does luteal-phase length matter for implantation and early pregnancy?

- What causes a short luteal phase—and which ones can you change today?

- Hormonal or medical drivers you can test

- Lifestyle factors within your control

- Which natural strategies are backed by science for lengthening the luteal phase?

- Nutrient powerhouses

- Herbal ally

- Stress-taming tactics

- Exercise reset

- Fertility-plate eating

- What medical treatments exist, and what does the evidence really say?

- Where does the research fall short, and how can you bridge the gap?

- When should you see a fertility specialist, and what tests will they run?

- Your top questions, answered

- Final thoughts

- References

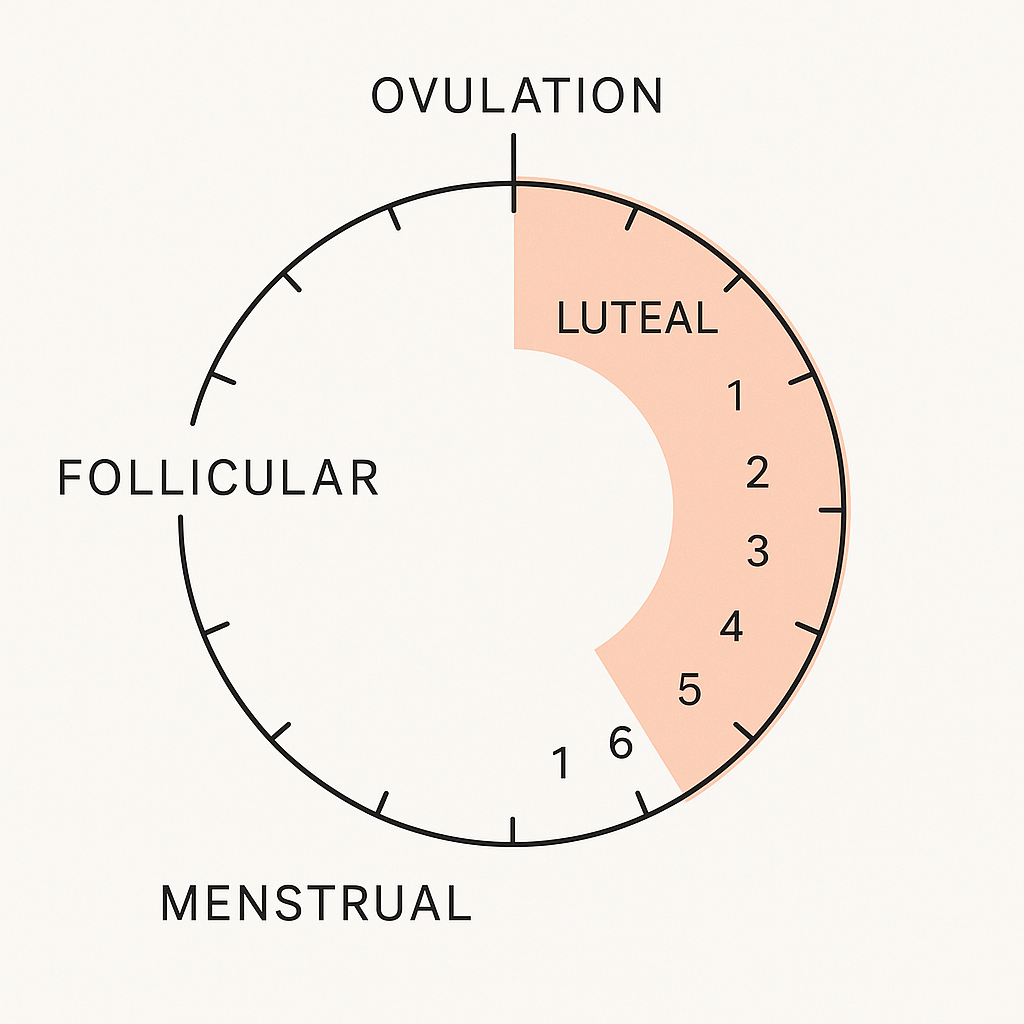

What is considered a short luteal phase, and how can you tell if yours is too short?

A short luteal phase is defined as a luteal phase lasting 10 days or fewer, measured from the day after ovulation to the day before your next period. This phase is crucial because it provides the hormonal environment needed for an embryo to implant and for early pregnancy to be supported. If your luteal phase is consistently less than 10 days, it may be too short to allow for successful implantation, which can contribute to infertility or early miscarriage. You can suspect a short luteal phase if your period starts less than 10 days after ovulation, especially if this pattern repeats over several cycles.

How long is “normal”?

A normal luteal phase typically lasts between 11 and 13 days, with an average of about 14 days. Cycles with a luteal phase of 9 days or less are almost always considered abnormal, while 10-day phases are abnormal in most cases. Only a small percentage of cycles naturally have a short luteal phase—about 5–9% in regularly menstruating women.

Why does the corpus luteum set the clock?

The corpus luteum is a temporary gland formed from the follicle after ovulation. It produces progesterone, which is essential for preparing the uterine lining for implantation and maintaining early pregnancy. The lifespan of the corpus luteum determines the length of your luteal phase; if it breaks down early or does not function properly, progesterone levels drop, and your period starts sooner, shortening the luteal phase. Inadequate formation or early regression of the corpus luteum is a key cause of a short luteal phase.

How can you measure your own luteal phase?

To measure your luteal phase, first identify your ovulation day using ovulation predictor kits (which detect the LH surge), basal body temperature tracking, or fertility apps. The luteal phase starts the day after ovulation and ends the day before your next period. Count the number of days in this interval for each cycle. Blood tests for progesterone, ideally 6–8 days after ovulation, can confirm ovulation and help assess luteal function, but hormone levels can fluctuate significantly, so timing is important. Endometrial biopsy is another method, but it is less commonly used due to its invasiveness and variability in interpretation. If you notice your luteal phase is consistently short, consult a healthcare provider for further evaluation and support.

Understanding the Implantation Window helps you see why even a two-day loss can close the door before an embryo arrives.

Why does luteal-phase length matter for implantation and early pregnancy?

The luteal phase is the part of the menstrual cycle after ovulation, when the corpus luteum produces progesterone to prepare the uterine lining (endometrium) for a potential embryo. A sufficiently long luteal phase (typically at least 11–13 days) ensures that the endometrium becomes thick, stable, and receptive, creating the optimal “window of implantation” for an embryo to attach and begin development.

If the luteal phase is too short, the endometrium may not be fully prepared or may start to break down before the embryo can implant, reducing the chances of successful implantation. Clinical studies show that prolonging the luteal phase with progesterone or similar hormones can increase endometrial thickness and improve implantation rates, especially in women with recurrent implantation failure or those undergoing assisted reproduction.

After implantation, the corpus luteum must continue producing progesterone to maintain the uterine lining and support the early stages of pregnancy until the placenta takes over hormone production. If the luteal phase is too short or progesterone levels drop prematurely, the endometrium may shed, leading to early pregnancy loss or miscarriage. Research in both natural and assisted cycles shows that supporting the luteal phase with progesterone increases the likelihood of ongoing pregnancy and live birth.

However, while a short luteal phase can reduce the chance of pregnancy in the immediate cycle, its long-term impact on overall fertility is less clear, as some women with short luteal phases can still conceive over time. In summary, an adequate luteal phase is essential first for successful implantation and then for maintaining early pregnancy until the placenta can sustain it.

To see how hormones choreograph this timeline, visit Key Hormones: Estrogen, Progesterone, Testosterone and Healthy Uterine Lining: Why Thickness Matters.

What causes a short luteal phase—and which ones can you change today?

A short luteal phase can be caused by a combination of hormonal, medical, and lifestyle factors—some of which you can address right away.

Hormonal or medical drivers you can test

Short luteal phases often result from inadequate progesterone production by the corpus luteum, which may be due to poor follicle development before ovulation or insufficient luteinizing hormone (LH) support after ovulation. Medical conditions such as thyroid disorders, high prolactin levels (hyperprolactinemia), and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) can also disrupt hormone balance and shorten the luteal phase.

Testing for these conditions typically involves blood tests to measure progesterone, LH, FSH, thyroid hormones, and prolactin, as well as ultrasound to assess follicle size and ovulation quality. In some cases, a small or poorly developed follicle can predict a short luteal phase, and a history of early menarche or high body mass index (BMI) may also be associated with luteal abnormalities. If you suspect a medical or hormonal cause, consult a healthcare provider for targeted testing and treatment.

Lifestyle factors within your control

Several lifestyle factors can contribute to a short luteal phase, and many are modifiable. High levels of physical or emotional stress can disrupt the hormonal signals needed for proper ovulation and luteal function. Strenuous or excessive exercise, especially when combined with low body weight or rapid weight loss, is a well-documented cause of short luteal phases and other menstrual irregularities.

Maintaining a healthy weight, managing stress, and ensuring adequate nutrition can help support normal luteal function. If you are experiencing short luteal phases, consider moderating intense exercise, prioritizing stress reduction techniques, and focusing on balanced nutrition. Addressing these lifestyle factors can often improve luteal phase length and overall reproductive health.

Poor pelvic circulation can also play a role; simple stretches in Boost Uterine Blood Flow: Easy Moves and Tips may help.

Which natural strategies are backed by science for lengthening the luteal phase?

Nutrient powerhouses

Certain nutrients play a key role in supporting hormone balance and a healthy luteal phase. Adequate intake of B vitamins; especially vitamin B6, has been linked to improved progesterone production and longer luteal phases, likely by supporting ovulation and hormone synthesis. Zinc and magnesium are also important for ovarian function and hormone regulation.

While direct clinical trials on these nutrients and luteal phase length are limited, observational studies suggest that women with higher intakes of these micronutrients may have more regular cycles and better luteal function. Ensuring a balanced diet rich in whole grains, leafy greens, nuts, seeds, lean proteins, and healthy fats can help provide these essential nutrients and support overall reproductive health.

Herbal ally

Among herbal remedies, vitex agnus-castus (chasteberry) is the most studied for luteal phase support. Research suggests that vitex may help lengthen the luteal phase by supporting the body’s natural production of progesterone, possibly by influencing the pituitary gland to balance LH and FSH secretion. Some small clinical trials and reviews have found that vitex can improve cycle regularity and luteal phase length, particularly in women with mild luteal phase defects or premenstrual symptoms.

However, while promising, the evidence is not as robust as for medical progesterone supplementation, and results can vary between individuals. If considering herbal supplements, it’s important to consult a healthcare provider, especially if you are trying to conceive or taking other medications.

Stress-taming tactics

Managing stress is important for reproductive health, as high stress levels can disrupt hormonal balance and potentially shorten the luteal phase. Regular aerobic exercise has been shown to significantly reduce perceived stress and improve mood during the luteal phase, helping to normalize emotional fluctuations and potentially support more stable menstrual cycles. Mindfulness practices, relaxation techniques, and ensuring adequate sleep are also beneficial for lowering stress and supporting hormonal health.

Exercise reset

While moderate aerobic exercise is beneficial for mood, stress reduction, and menstrual regularity, excessive or strenuous exercise; especially when combined with low energy intake, can lead to luteal phase defects or even missed periods. The key is to find a balance: regular, moderate-intensity exercise supports overall reproductive health, but overtraining or rapid increases in exercise intensity should be avoided to prevent disruptions in the luteal phase.

If you notice cycle changes after increasing exercise, consider scaling back or ensuring you are eating enough to meet your energy needs. Gentle movement keeps Uterine Contractions: Good vs. Bad Cramps Explained in the “good” zone.

Fertility-plate eating

Diet quality and specific nutrients play a role in luteal phase health. Diets high in dietary restraint or low in energy availability are linked to shorter luteal phases. A balanced, nutrient-rich diet, sometimes called a “fertility plate” should include lean proteins, healthy fats, whole grains, fruits, and vegetables, with adequate selenium, zinc, and B vitamins to support hormone production and endometrial health.

The Mediterranean diet, while generally healthy, was associated with a higher risk of luteal phase deficiency in one study, possibly due to higher fiber or isoflavone intake, which may affect hormone metabolism2. Ensuring sufficient caloric intake and avoiding overly restrictive diets are key steps you can take today to support a healthy luteal phase.

What medical treatments exist, and what does the evidence really say?

Medical treatments for a short luteal phase primarily focus on supplementing or supporting progesterone, the hormone essential for preparing and maintaining the uterine lining for implantation and early pregnancy. The most common and evidence-backed approach is the use of:

Micronized progesterone is a standard treatment for luteal phase support, especially in assisted reproduction. Both oral and vaginal forms are used, with recent studies showing that oral micronized progesterone (400 mg/day) is non-inferior to vaginal progesterone gel for supporting ongoing pregnancy rates in fresh embryo transfer cycles, making it a viable alternative for those who prefer oral administration. In frozen embryo transfer and letrozole-hCG cycles, combining vaginal micronized progesterone with oral dydrogesterone may further improve live birth rates and reduce miscarriage compared to vaginal progesterone alone. In intrauterine insemination (IUI) cycles using letrozole, oral progesterone support significantly increases live birth and clinical pregnancy rates, though its benefit in IUI cycles with clomiphene citrate or in normo-ovulatory women is less clear.

Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) can be used to trigger ovulation and support the luteal phase by stimulating the corpus luteum to produce progesterone. In letrozole-hCG cycles, hCG is administered when the dominant follicle is mature, and this approach is effective for endometrial preparation and luteal support in frozen embryo transfer protocols. However, hCG is less commonly used for ongoing luteal support due to the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, especially in high-responder patients.

Clomiphene citrate and letrozole are oral ovulation induction agents. Letrozole is often preferred for women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or those undergoing IUI, as it is associated with higher pregnancy rates and a lower risk of multiple gestations. Luteal phase support with progesterone is beneficial in letrozole-stimulated cycles, improving live birth and clinical pregnancy rates. In contrast, routine progesterone supplementation in clomiphene-stimulated IUI cycles does not appear to improve pregnancy outcomes in normo-ovulatory women.

Thyroid dysfunction, particularly hypothyroidism, can cause menstrual irregularities and luteal phase defects. Treating underlying thyroid disorders with levothyroxine or other thyroid medications can restore normal ovulatory cycles and improve luteal phase length and fertility outcomes. Thyroid function should be routinely assessed in women with short luteal phases or unexplained infertility.

Metformin is an insulin-sensitizing agent commonly used in women with PCOS, a condition often associated with luteal phase defects and anovulation. By improving insulin sensitivity and reducing androgen levels, metformin can help restore regular ovulation, lengthen the luteal phase, and improve fertility outcomes in women with PCOS. It is not typically used for luteal phase support in women without PCOS.

Cabergoline is a dopamine agonist used to treat hyperprolactinemia, a condition that can suppress ovulation and shorten the luteal phase. By lowering prolactin levels, cabergoline can restore normal ovulatory cycles and improve luteal function, making it an important treatment for women with elevated prolactin and associated menstrual disturbances.

Addressing underlying endocrine issues is essential when these conditions are present, as they can directly impact luteal phase health and fertility.

Where does the research fall short, and how can you bridge the gap?

Research on short luteal phase treatment faces several key gaps.

First, there is no universally accepted definition or diagnostic test for luteal phase defect, making it difficult to identify which patients truly need treatment and to compare results across studies. The relationship between short luteal phase and infertility or recurrent pregnancy loss remains controversial, with inconsistent evidence on whether correcting luteal phase length improves outcomes, especially in natural (non-ART) cycles.

Most research and clinical protocols focus on assisted reproductive technology (ART), where luteal phase support is standard, but even here, optimal timing, dosing, route, and duration of progesterone or hCG supplementation are not well established, and real-world practices often diverge from evidence-based recommendations.

There is also limited research on individualized luteal phase support tailored to patient characteristics or hormone levels, though early studies suggest this may improve outcomes for some women. Additionally, the evidence base for alternative agents (like oral progestins, subcutaneous progesterone, or add-on therapies) is still evolving, and cost-effectiveness and patient preference are rarely addressed.

To bridge these gaps, future research should focus on developing reliable diagnostic criteria, conducting high-quality randomized trials in both ART and natural cycles, and exploring personalized treatment approaches based on individual hormone profiles and risk factors. Collaboration between researchers and clinicians is needed to align guidelines with real-world practice and ensure that treatments are both evidence-based and patient-centered.

Immune cross-talk also matters—see Immunity and Fertility: Can Your Body Reject Pregnancy? for another layer to explore.

When should you see a fertility specialist, and what tests will they run?

You should see a fertility specialist if you are under 35 and have not conceived after 12 months of regular, unprotected intercourse, or after 6 months if you are over 35. Immediate evaluation is recommended for women over 40 or anyone with known risk factors for infertility, such as irregular cycles, endometriosis, or a history of pelvic surgery or infection.

The initial workup includes a detailed medical history and physical exam for both partners. For women, tests typically assess ovulation (such as hormone blood tests), ovarian reserve (like AMH or FSH levels), and structural issues (using pelvic ultrasound or imaging to check the uterus and fallopian tubes). For men, a semen analysis is standard, and further tests may be ordered if abnormalities are found. Additional male tests can include sperm DNA fragmentation or other specialized assessments in certain cases. Partner’s semen analysis—review Sperm Morphology Basics.

Both partners may also be screened for infections or genetic conditions if indicated. The goal is to identify treatable causes and guide appropriate therapy, with unexplained infertility diagnosed only after normal results in ovulation, tubal patency, and semen analysis. Early referral and comprehensive testing can improve the chances of successful treatment and reduce unnecessary delays.

Your top questions, answered

Is an 11-day luteal phase too short?

An 11-day luteal phase is on the shorter end of the normal range, which is typically 11 to 17 days. While some women with an 11-day luteal phase conceive without difficulty, a consistently short luteal phase may reduce the chances of implantation and successful pregnancy, especially if it is accompanied by other symptoms or fertility challenges.

Can stress alone shorten my luteal phase?

Chronic or severe stress can disrupt hormonal balance and potentially shorten the luteal phase by affecting the release of reproductive hormones. However, stress is rarely the sole cause; it often interacts with other factors such as nutrition, exercise, or underlying health conditions to impact menstrual cycles.

Do I need IVF if supplements fail?

IVF is not always necessary if supplements like progesterone do not resolve a short luteal phase. Many women benefit from less invasive treatments or addressing underlying issues such as thyroid dysfunction, PCOS, or lifestyle factors. IVF is typically considered after other options have been exhausted or if there are additional fertility barriers.

How fast can lifestyle changes help?

Positive lifestyle changes such as reducing stress, improving diet, and moderating exercise can sometimes improve luteal phase length and menstrual regularity within a few cycles, though the exact timeline varies by individual. Consistency is key, and improvements may be seen as early as one to three months after making changes.

Final thoughts

A short luteal phase, typically defined as less than 10 or 11 days, can be concerning for those trying to conceive, but current research suggests its impact is nuanced. Isolated short luteal phases are relatively common and may temporarily lower the chance of pregnancy in the following cycle, but do not appear to significantly increase the risk of infertility or miscarriage over the long term. In regularly menstruating women, both clinical (short duration) and biochemical (low progesterone) luteal phase deficiencies exist, but they may reflect different underlying hormonal patterns, and recurrent short luteal phases are uncommon.

The relationship between short luteal phases and overall cycle irregularity, especially in perimenopausal women, is not well established and may require larger studies for clarification. Hormonal imbalances, such as lower estradiol, FSH, and LH, are often associated with short luteal phases, suggesting a spectrum of ovulatory function rather than a single defect.

For most women, a single or occasional short luteal phase is not a cause for alarm. However, persistent or recurrent short luteal phases, especially when accompanied by other symptoms or fertility challenges, may warrant further evaluation. Ultimately, while a short luteal phase can be a piece of the fertility puzzle, it is rarely the sole factor, and a comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment is recommended.

Download our free “Three-Cycle Luteal Tracker,” explore the Follicle Growth Chart: Week-by-Week Overview, and take the next confident step toward the family you envision.

References

-

Does a short luteal phase correlate with an increased risk of miscarriage? A cohort study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05195-9

-

The role of short luteal phases on cycle regularity during the perimenopausal transition. Menopause, 32, 258 - 265. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000002477

-

Hormonal Predictors of Abnormal Luteal Phases in Normally Cycling Women. Frontiers in Public Health, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00144

-

Individualized luteal phase support after fresh embryo transfer: unanswered questions, a review. Reproductive Health, 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01320-7

-

Luteal Phase Defects and Progesterone Supplementation. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 79, 122 - 128. https://doi.org/10.1097/OGX.0000000000001242

-

Luteal phase support in assisted reproductive technology… Nature reviews. Endocrinology. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-023-00921-5

-

Luteal Phase Support in IVF: Comparison Between Evidence-Based Medicine and Real-Life Practices. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.00500

-

Individualised luteal phase support in artificially prepared frozen embryo transfer cycles based on serum progesterone levels: a prospective cohort study… Human reproduction. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deab031

-

Luteal Phase Support Using Subcutaneous Progesterone: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Reproductive Health, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/frph.2021.634813

-

A 10-year follow‐up on the practice of luteal phase support using worldwide web‐based surveys. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology : RB&E, 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-021-00696-2

-

The Role of Dydrogesterone in the Management of Luteal Phase Defect: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus, 15.