Parents often search for “baby IQ test” every 30 seconds, seeking insights into their child’s future intelligence. However, scores from tests taken in the first two years primarily reflect current developmental status and have limited ability to predict long-term cognitive outcomes. This guide explores what these tests measure, their reliability, and how parents can support their baby’s cognitive growth effectively, drawing on scientific evidence and practical advice.

- What exactly are “baby IQ tests,” and how are they different from regular developmental check-ups?

- Are we really talking about IQ or something else?

- How did infant testing evolve?

- How reliable are baby IQ scores before age 4?

- What can early testing tell you now—and what can’t it predict later?

- When does it actually make sense to test an infant or toddler?

- How are scores reported, and what do the numbers really mean?

- Could labeling early scores hurt—or help—your child?

- Which factors actually shape future intelligence more than a test score?

- What should you focus on instead of the number?

- How can you support cognitive growth day-to-day?

- Fast FAQ: Your top questions answered

- Conclusion: Do Baby IQ Tests Shape Your Child’s Future?

What exactly are “baby IQ tests,” and how are they different from regular developmental check-ups?

Are we really talking about IQ or something else?

Most assessments for infants under 3 years measure a Developmental Quotient (DQ) or Developmental Index (DI), not a true Intelligence Quotient (IQ). Instruments like the Bayley Scales of Infant & Toddler Development and Mullen Scales of Early Learning evaluate skills in motor, language, and problem-solving domains relative to same-age peers. These differ from traditional IQ tests, such as the Stanford-Binet or Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI), which are typically administered starting at age 2 ½ and offer greater reliability after age 4.

Traditional IQ batteries—Stanford-Binet or the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI)—start around 2 ½ years, with best reliability after age 4.

How did infant testing evolve?

In the 1980s, Joseph Fagan’s studies on “novelty preference” suggested that infants’ attention to new stimuli might indicate cognitive ability, fueling commercial interest. Quick IQ screens appeared in malls, but subsequent research revealed their poor predictive accuracy, leading to their decline.

For a deeper dive into how babies acquire knowledge, see How Your Baby’s Brain Learns.

How reliable are baby IQ scores before age 4?

Not very. Research indicates that IQ scores before age 4 are not strong predictors of future intelligence. A study published in 2018 found that cognitive scores at age 1 account for only about 3% of IQ variance at age 6, while age-2 scores account for approximately 21% (correlation ≈ 0.46). Factors like rapid synaptogenesis, naps, teething discomfort, or hunger can cause score fluctuations of 15–20 points.

Individually administered tests by trained psychologists are more reliable than group screeners due to controlled conditions and personalized observation. However, premature or medically fragile infants often exhibit wider score variations, particularly those born before 32 weeks gestation. Examples of such variability are discussed in Baby IQ vs. Milestones.

What can early testing tell you now—and what can’t it predict later?

-

Can tell: Early tests can identify whether a child is meeting language, motor, and social milestones on time. Detecting delays early allows for interventions like speech or occupational therapy, which improve outcomes for about 30% of toddlers with initial delays, according to pediatric research.

-

Cannot tell: These tests cannot reliably predict academic placement, college admissions, or lifelong cognitive potential. Brain plasticity, driven by neural connections and environmental influences, continues to shape development into adolescence.

For example, Ava, born at 28 weeks, scored 78 on her DI at 10 months corrected age. After speech therapy and parent-led “serve-and-return” interactions, her score reached 98 by age 5.

When does it actually make sense to test an infant or toddler?

Test if you notice red flags such as:

- Premature birth (<32 weeks) or low birthweight.

- Missed milestones (no babbling by 12 months, no walking by 18 months).

- Loss of previously gained skills.

- Strong family history of developmental disorders.

Developmental screenings are valuable whenever concerns arise, while predictive IQ testing is most reliable between ages 6 and 8. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends ongoing developmental surveillance during well-child visits.

Common pitfalls—like waiting for “just one more month”—are covered in 7 Parenting Mistakes That Harm Your Baby’s Brain Growth.

How are scores reported, and what do the numbers really mean?

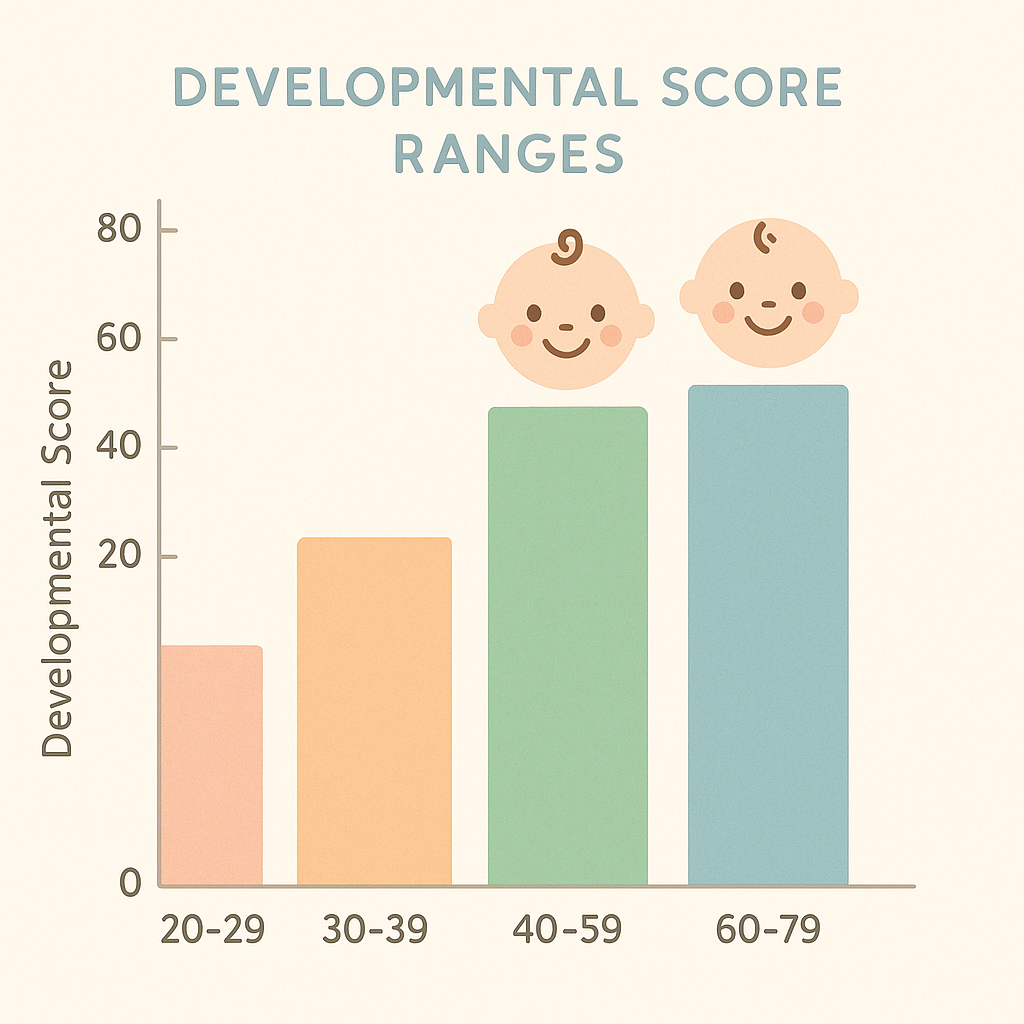

Scores are standardized around a mean of 100 with a 15-point standard deviation. For preterm infants, “corrected age” is used until 24–36 months to ensure fair comparisons and reported as follows:.

| Score Range | Interpretation (Provisional) |

|---|---|

| 70–84 | Below average, possible delay |

| 85–115 | Average (68% of infants) |

| 116–130 | Above average |

| >130 | Possible giftedness (interpret cautiously) |

Could labeling early scores hurt—or help—your child?

Risks of Labeling: Labeling early scores can lead to a fixed mindset, increase parental stress, or reflect cultural biases in testing. A Hechinger Report investigation highlighted cases where over-reliance on early IQ scores restricted access to special-education services.

Benefits of Scores: When used appropriately, scores can secure insurance-covered therapies, qualify children for research programs, or monitor progress. Parents should view results as temporary data points, not definitive predictors.

Which factors actually shape future intelligence more than a test score?

Several factors outweigh early test scores in influencing cognitive development:

- Genetics: Maternal IQ is a strong predictor, particularly in high-socioeconomic-status (SES) families, explaining up to 24% of IQ variance at age 5. See PLOS One, 2013.

- Language Exposure: Frequent “conversational turns” at 18–24 months correlate with higher verbal IQ a decade later, according to LENA research.

- Nutrition: Deficiencies in iron or DHA can reduce scores by up to 10 points, as shown in studies on cognitive development.

- Stress: Elevated parental stress may contribute to smaller child vocabularies, potentially through disrupted parent-child interactions as per ScienceDirect, 2023.

Find science-backed enrichment ideas in 10 Proven Ways to Boost Your Baby’s Intelligence.

What should you focus on instead of the number?

Instead of the numbers, do the following:

- Responsive Interaction: Engage in frequent talking, reading, and singing to strengthen neural connections. Mimicking your baby’s coos fosters language acquisition and emotional bonding.

- Sensory Play: Encourage activities like tummy time, water splashing, or nature walks to stimulate sensory and motor development, enhancing synaptic pruning.

- Stress Management: Calm caregivers promote optimal brain development. Managing parental stress supports a nurturing environment, as stress can indirectly affect language development.

For a full roadmap, explore The Ultimate Guide to Boosting Your Baby’s Brain Power.

How can you support cognitive growth day-to-day?

Incorporate these evidence-based habits:

- Conversational Turns: Aim for 20 back-and-forth exchanges daily to boost language skills.

- Toy Rotation: Switch toys weekly to engage novelty-seeking circuits.

- Rhythm Games: Clap or bounce to music to enhance auditory mapping.

- Nutrient-Rich Diet: Provide foods high in DHA, choline, and zinc during the first 1,000 days to support brain growth.

Fast FAQ: Your top questions answered

-

When Are IQ Tests Most Accurate?

Tests are most reliable at ages 6–8. Scores stabilize as neural connections mature, per a 2016 Developmental Psychology study. -

Do Bilingual Homes Affect Scores?

Early verbal scores may be lower, but bilingual children often show stronger executive function and similar or higher IQ by adolescence. -

Can a Low DQ Improve?

Yes, with intervention. Plasticity and therapies like speech or motor training close gaps in 2–3 years for most children. -

Are Online IQ Quizzes Valid?

No, they’re not reliable. Online quizzes lack standardization and oversight. Read more in Boosting Baby IQ: 5 Myths Debunked.

Conclusion: Do Baby IQ Tests Shape Your Child’s Future?

Baby IQ tests serve as snapshots, not a destiny. They can help identify developmental delays early, but their predictive power for future intelligence is limited. Instead of focusing on scores, parents should prioritize rich interactions, sensory play, proper nutrition, and stress management. These factors build the curiosity, resilience, and joy that drive lifelong learning, far outweighing the importance of any number.